New York Giants’ Mathias Kiwanuka tackles the value of playing for others:

Touching takeaways from a two-time champion

SHI employees were recently invited into the huddle with two-time Super Bowl champion Mathias Kiwanuka, former linebacker and defensive end for the New York Giants. The football great spoke at our New Jersey headquarters to commemorate Black History Month at an event sponsored by HP, Jamf, Viewsonic, and SHI’s Black Culture Collective. In an interview with the group’s own Rob Williams and Kevin English, Kiwanuka shared lessons from a career that spanned decades and a family that spans continents.

Nothing shapes you like family

Before he was 2004 First-team All-American and Big East Defensive Player of the Year, he was just Mathias. Well, maybe not just Mathias. Kiwanuka is grandson to the first Prime Minister of Uganda, Benedicto Kiwanuka, who was granted the role when Uganda began international self-governance in 1962. Tragically, Benedicto was assassinated by political opponents, over ten years before Mathias’ birth. Despite being born in Indianapolis, Mathias’ mind is never far from his Ugandan family. He told SHI employees that he finds inspiration in how his grandfather “stood behind his words” and “sacrificed his life” for something bigger than himself.

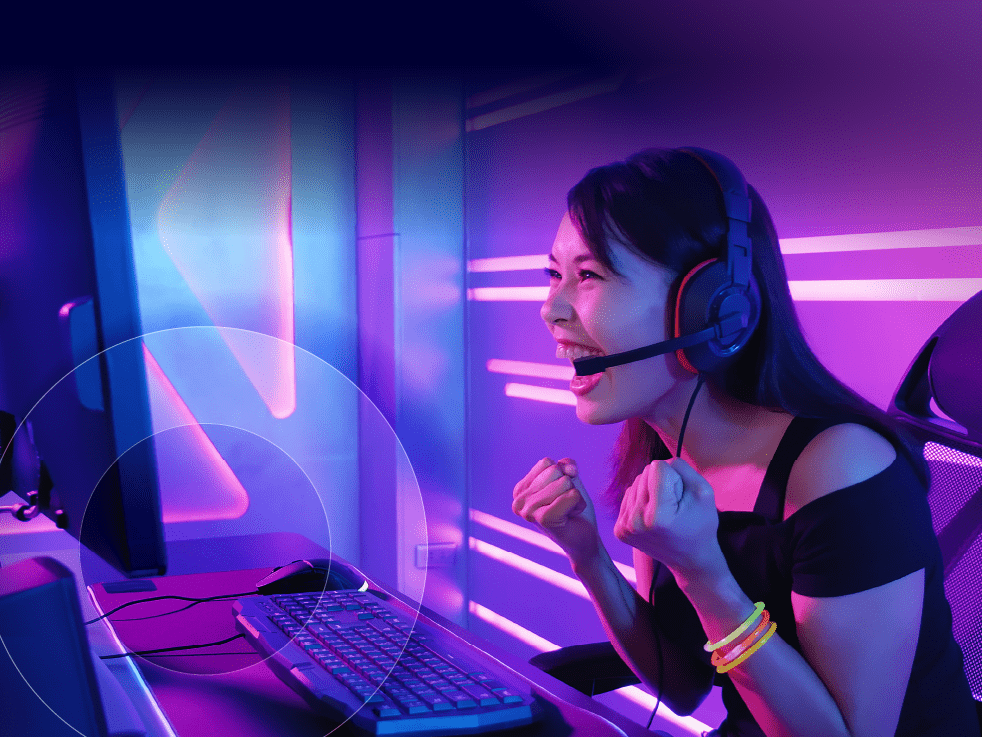

Mathias Kiwanuka discusses the importance of self-discipline with Robert Williams and Kevin English.

Just as Benedicto’s legacy shaped him, so too did his parents. One of three children himself, he was molded by Ugandan customs instilled in him by his mother and father. But while Kiwanuka may have been learning Ugandan traditions at home, the America outside of it was teaching him about a sinister tradition of its own. He recalls “always being reminded [he was] different,” not as an African but “as a Black American.” In the face of the same systemic issues that dogged much of Black America, Kiwanuka pushed forward, focusing his attention on what would come to define his future: football. Not the kind of football his Ugandan family initially preferred but football nonetheless.

Family, however, defines his present more than anything. Now father to a young son and daughter, Kiwanuka highlighted the kind of impact he’s made on them by practicing the values he wants them to practice too: good self-conduct and the use of their talents for the betterment of others.

“Anxiety is eased by preparation”

Kiwanuka’s own talent as a defensive end was nothing if not impactful, a fact his alma mater Boston College recognized. But it wasn’t until his redshirt year at BC that Kiwanuka “took it to the next level.” Hard work took on new meaning as he made a name for himself despite historically “never being the biggest or fastest kid.” He soon had his eyes on an even higher level though, and on NFL Draft Day, he was the final pick of the first round, chosen by the New York Giants: a team that already had three Pro Bowlers in his position of defensive end. Luckily, head coach Tom Coughlin had something else in mind for Kiwanuka: the role of a linebacker.

SHI’s Austin-based employees enjoy a special social hour after watching Kiwanuka’s presentation together via webcast.

This change, in addition to being “back to the bottom” as an NFL rookie, brought on intense anxiety for Kiwanuka. And yet he “took on the challenge.” He practiced constantly, emphasizing that he “did even more work to make that transition” and “earn respect.” He even occasionally switched between defensive end and linebacker positions.

“Sports teaches you how to calm nerves,” Kiwanuka said. However, not even Super Bowl rings can make anxiety vanish completely. “Even after the championship,” he continued. “It’s stressful and stress doesn’t stop after championship.”

Physical health and mental health can connect in surprising ways

According to Kiwanuka, football is – for better or worse – “a high-octane business.” In his experience, no feeling is quite as addictive as sacking a quarterback. The QB is down, the crowd explodes with cheers, “but when the game is over and the cheers are gone, you have to find another way to get back up in the morning.” Many players, he said, struggle deeply with that transition, himself included. And as Kiwanuka knows all too well, any mental toll of accomplishment is nothing when compared to that of an injury.

During his second season with the Giants in 2007, Mathias Kiwanuka fractured his left fibula, and was forced to celebrate their Super Bowl victory from the sidelines. When speaking about his recovery to SHI employees, he referenced talk therapy’s key role alongside any physical therapy, both helping him bounce back from depression. While his family offered crucial support at the time, Kiwanuka advocates for therapy to play a part in the lives of non-athletes as well, and cited the benefits of this objective, nonjudgmental presence in people’s lives.

Despite his fibula not being his only (or even his worst) injury, after years of mental and physical work, vindication was waiting in the wings. Kiwanuka took the field in February 2012, and secured his second Super Bowl ring, which he wore proudly during his talk with SHI staff.

Find strength in community

Since retiring from the NFL in 2015, Kiwanuka has traded his blood, sweat, and tears for a business that’s a little sweeter: wine. But being his own boss doesn’t mean the hard work (or his infallible work ethic) went into retirement too. As Kiwanuka started Wandering Wines, the same hands that sport two Super Bowl rings also loaded countless crates of wine and drove the trucks he put them in.

But more than motivation, Kiwanuka mentioned community – specifically the Black community – as integral to kicking off his business.

“If you’re willing to reach out to people, people are willing to help,” he said. “They want to see you succeed. When you connect with people of color, things can get easier.”

To that end, Kiwanuka isn’t just thinking about paying employees; he’s paying it forward. For over a decade, he has been helping give back in impactful ways, including continuing his grandfather’s vision for a more educated Uganda. Mathias was instrumental in helping build out a village’s school, noting it was what that community said they needed, not what others thought they needed. More globally, he’s also done work with Smile Train: a nonprofit providing corrective surgery for children’s cleft lips and palates. And yes, he does occasionally coach flag football too.

Like Kiwanuka, SHI’s Black Culture Collective members appreciate the power of communal support as well as diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives that put effort behind their words. One SHI employee found his talk to be a “powerful story of the Black experience” that was both “inspirational and needed.” Others cited his refusal to “let a setback become a roadblock” and his efforts to “give back to the community at large.” However, Mathias Kiwanuka may have incidentally given his audience the ultimate winning strategy as he explained the game he loves so much: “You can’t play for you.”